Special to CosmicTribune.com, July 21, 2025

Excerpts from weekly Sky&Telescope report.

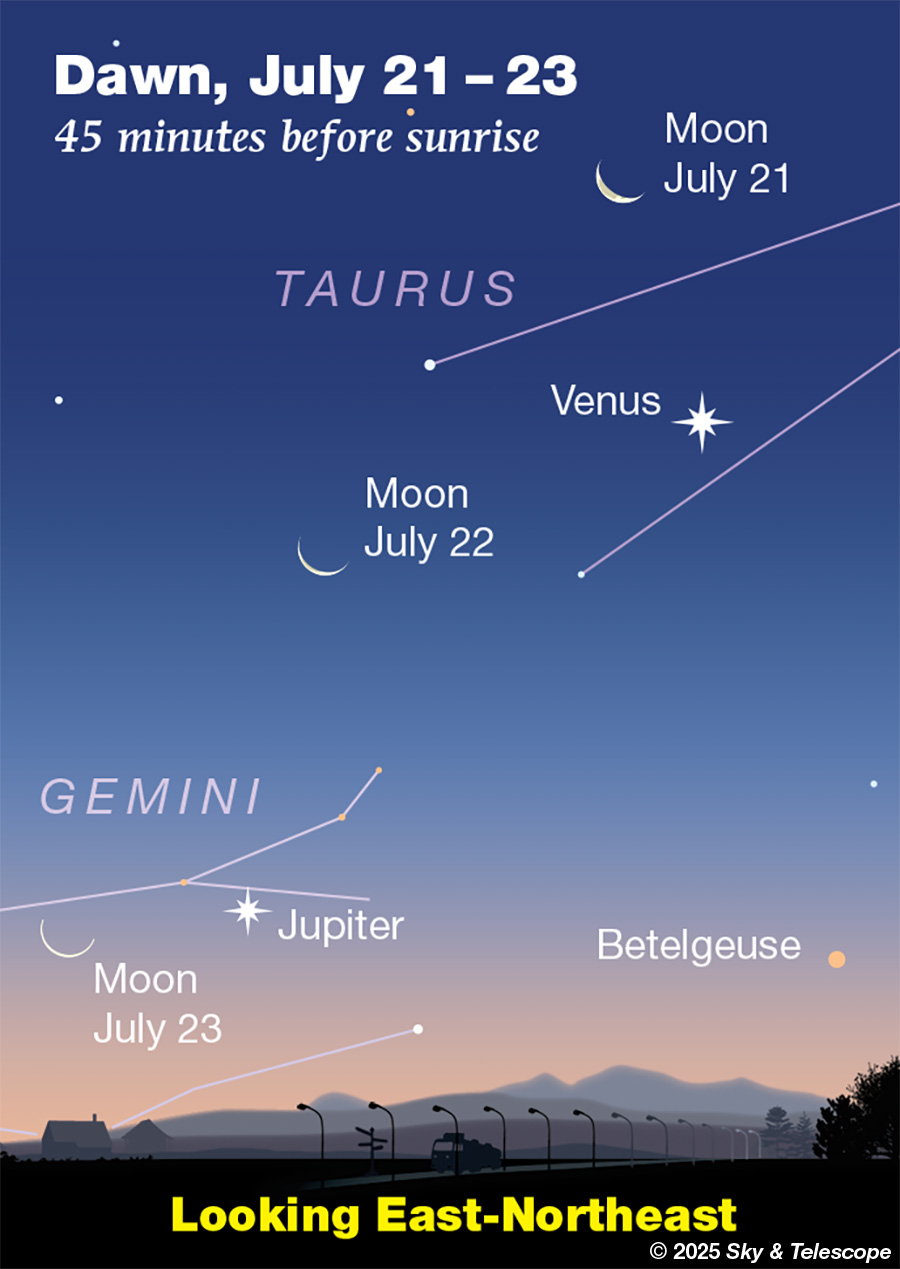

The waning crescent Moon in the dawn passes Venus, then Jupiter. Look before or during early dawn, while the sky is still pretty dark, to spot the horntips of Taurus a well as the rest of Taurus off the frame to the upper right.

The waning crescent Moon in the dawn passes Venus, then Jupiter. Look before or during early dawn, while the sky is still pretty dark, to spot the horntips of Taurus a well as the rest of Taurus off the frame to the upper right.

MONDAY, JULY 21

■ As dawn begins to brighten on Tuesday morning the 22nd, look east-northeast for the thin crescent Moon with Venus shining to its upper right, as shown above. Forming a quadrilateral with them are the two horntip stars of Taurus: Beta and lesser Zeta Tauri, shown in the illustration.

Far below them all, catch Jupiter coming up.

TUESDAY, JULY 22

■ Cassiopeia is now well past its bottoming-out for the year. Look for its tilted W pattern low-ish in the north-northeast after dark. The farther north you live, the higher it will be.

■ Fourth star of the Summer Triangle. The next-brightest star near the three of the Summer Triangle, if you’d like to turn it into a diamond, is Rasalhague (Alpha Ophiuchi), the head of Ophiuchus. Look high toward the southeast soon after dark. You’ll find Rasalhague about equally far to the upper right of Altair and lower right of Vega.

Altair is currently the Summer Triangle’s lowest star. Vega is the highest and brightest.

Face southeast right after dark in July, look high, and there’s the big, Milky-Way-crossed Summer Triangle. Add Rasalhague to its right and you’ve got a cut diamond standing on its point. Bob King photo

Face southeast right after dark in July, look high, and there’s the big, Milky-Way-crossed Summer Triangle. Add Rasalhague to its right and you’ve got a cut diamond standing on its point. Bob King photo

WEDNESDAY, JULY 23

■ Standing atop Scorpius in the south after darkness is complete, and butting heads with Hercules much higher, is enormous Ophiuchus the Serpent-Holder. Just east of his east shoulder (Beta Ophiuchi) is a dim V-shaped asterism like a smaller, fainter Hyades. This is the defunct constellation Taurus Poniatovii, “Poniatowski’s Bull.” The V is 2½° tall and stands almost vertically now.

The top two stars of the V are the faintest (magnitudes 4.8 and 5.5). The middle star of its left (east) side is the famous K-dwarf binary 70 Ophiuchi, visual magnitudes 4.2 and 6.2, distance just 17 light-years. The two stars of the pair are currently 6.7 arcseconds apart in their 88-year orbit: close but nicely separated at medium-high power in any telescope.

Just 1¼° NNE of Beta Oph (Cebalrai) is the large, very loose open cluster IC 4665, a binocular target 1,100 light-years away. That’s relatively near for an open cluster, which accounts for its rather large apparent size; it’s a little more than ½° across.

If you orient your view so celestial SSW is up — in other words putting Beta Oph straight above the group — its central stars spell out a ragged welcome: “HI”.

(The “HI” will be in mirror writing if your view is mirror-reversed. That happens whenever your optical system has an odd number of reflections, such as if you use a star diagonal at the eyepiece.)

For more telescopic sights in this area, including Barnard’s Star, doubles in IC 4665, and two other clusters, see Ken Hewitt-White’s “Suburban Stargazer” section in the July Sky & Telescope, page 55. (The text there misidentifies Collinder 350 as “359”.)

THURSDAY, JULY 24

■ New Moon (exact at 3:11 p.m. EDT), and a new lunar month begins. Unlike the calendar month, which averages 30.437 days long, the lunar month (from one new Moon to the next) averages 29.531 days. This means that, on average, you’ll see the Moon in any given phase about one day earlier each month by the calendar.

■ In this dark of the Moon, learn the important, rich little Milky Way constellation Scutum, the Shield, off the tail of Aquila using Matt Wedel’s Binocular Highlight column “Challenging Scutum Clusters” in the August Sky & Telescope, page 43. With chart.

FRIDAY, JULY 25

■ As summer progresses, bright Arcturus moves down the western side of the evening sky. Its pale ginger-ale tint always helps identify it.

Arcturus forms the bottom point of the Kite of Boötes. The Kite, rather narrow, extends upper right from Arcturus by 23°, about two fists at arm’s length. The lower right side of the kite is dented inward, as if some invisible celestial intruder once banged it.

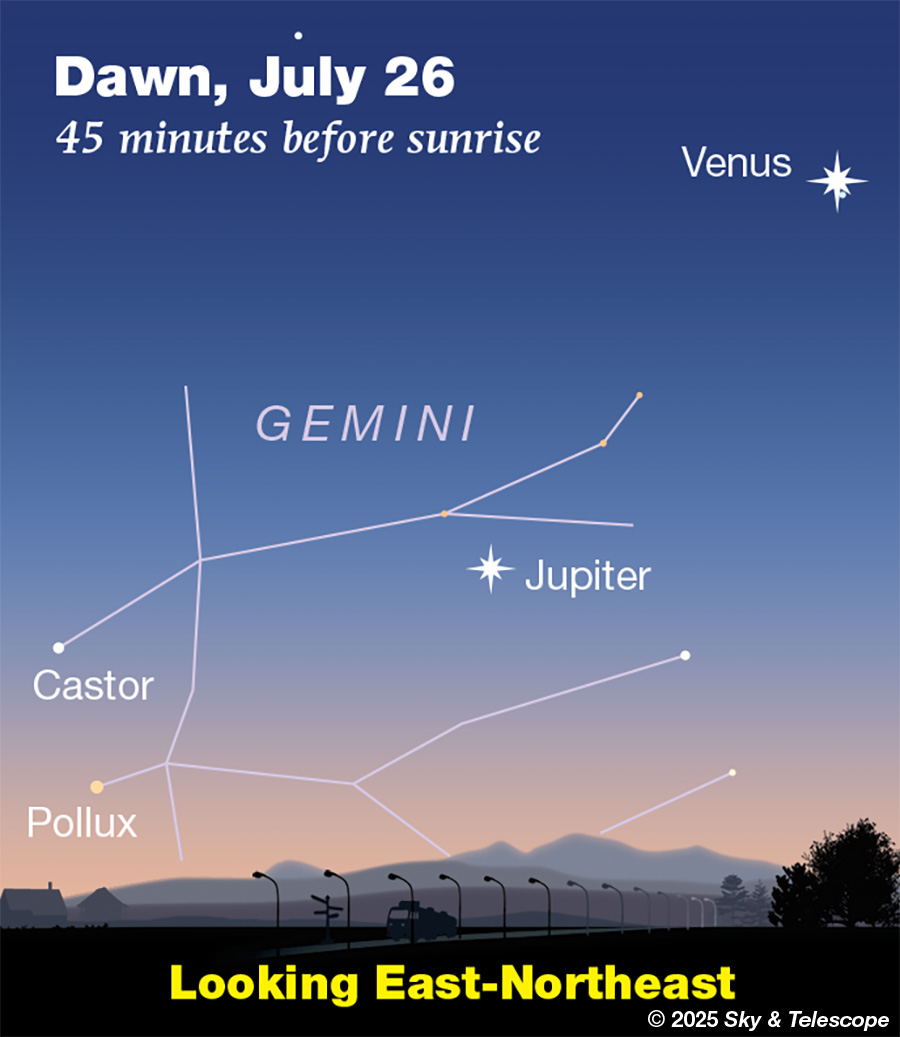

Venus and Jupiter are drawing closer together; they’re now only 16° apart. And both are getting higher.

Venus and Jupiter are drawing closer together; they’re now only 16° apart. And both are getting higher.

SATURDAY, JULY 26

■ Look again to Arcturus high in the west. In astronomy lore today, Arcturus may be best known for its cosmic history: It’s an orange giant some 7 billion years old, older than the Sun and solar system, racing by our part of space on a trajectory that indicates it was born in another galaxy: a dwarf galaxy that fell into the Milky Way and merged with it.

But in the astronomy books of our grandparents, Arcturus had a different claim to fame: It turned on the lights of the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago optimistically celebrating “a century of progress.” Astronomers rigged the newly invented photocell to the eye end of big telescopes around the US and aimed them where Arcturus would pass at the correct moment on opening night. Where the sky was clear the star’s light crept onto the cells, the weak signals were amplified and sent over telegraph wires to Chicago, and on blazed the massive lights to the cheers of tens of thousands.

Why Arcturus? Astronomers of the time thought it was 40 light-years away (the modern value is 36.7 ±0.2). So the light would have been in flight since the previous such great event in Chicago, the World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1893.

And earlier? Arcturus was famous as one of the first stars discovered to show proper motion, its own independent motion on the celestial sphere. In 1718 Edmond Halley realized that Arcturus, Sirius, and Aldebaran had moved more than half a degree from where the Greek astronomer Hipparchus measured them to be some 1,850 years earlier.

And before that? Arcturus was the first nighttime star to be seen in the daytime with a telescope: by Jean-Baptiste Morin in 1635.

SUNDAY, JULY 27

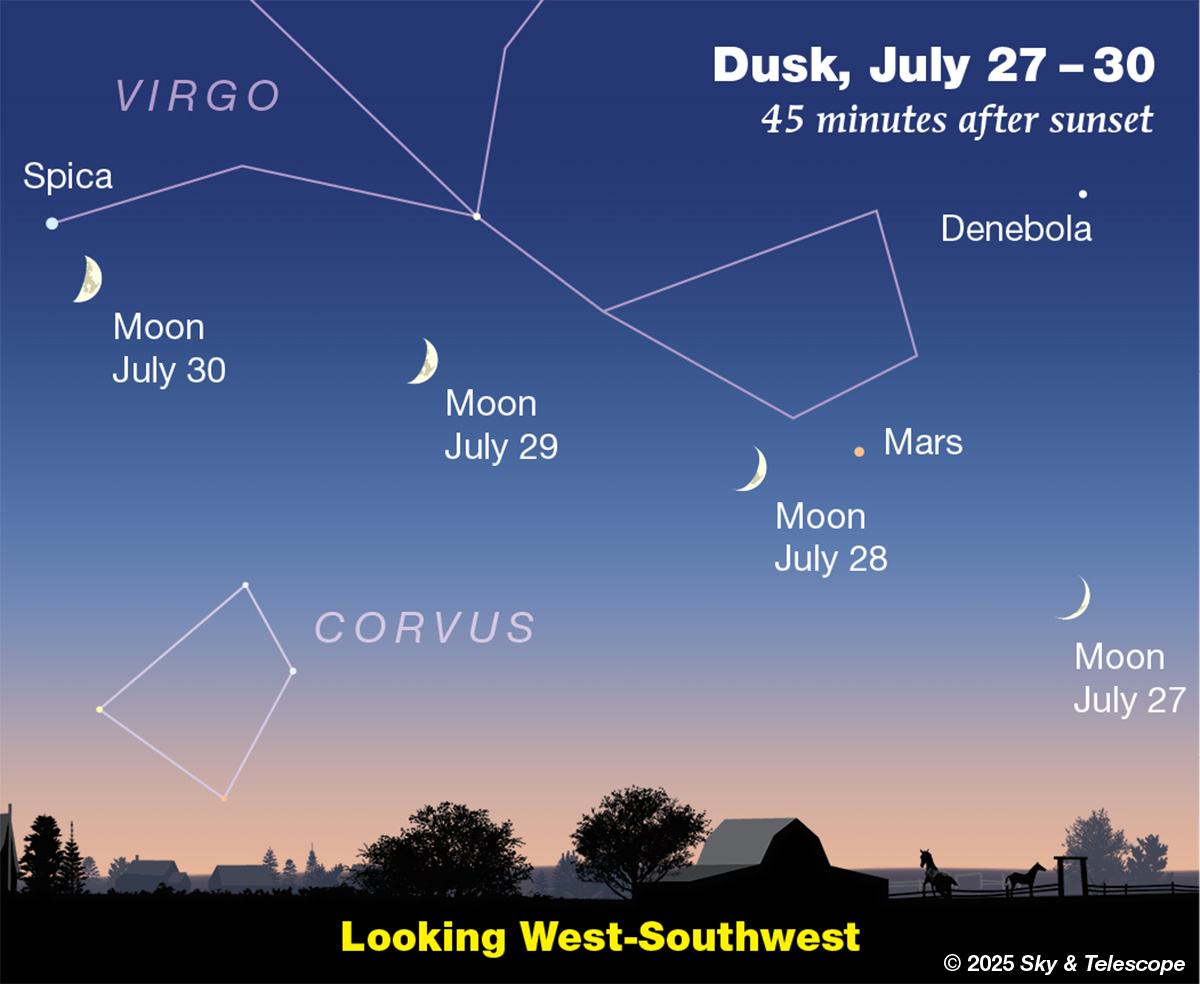

■ Use the crescent Moon to guide you to Mars and Denebola in the fading twilight this evening, as shown below.

At dusk in the next three days, the waxing crescent Moon moves from lower right of Mars to much closer lower right of Spica.

At dusk in the next three days, the waxing crescent Moon moves from lower right of Mars to much closer lower right of Spica.

■ At this time of year the Big Dipper hangs diagonally in the northwest after dark. From the Big Dipper’s midpoint, look three fists to the right to find Polaris, not very bright at 2nd magnitude, glimmering due north as always.

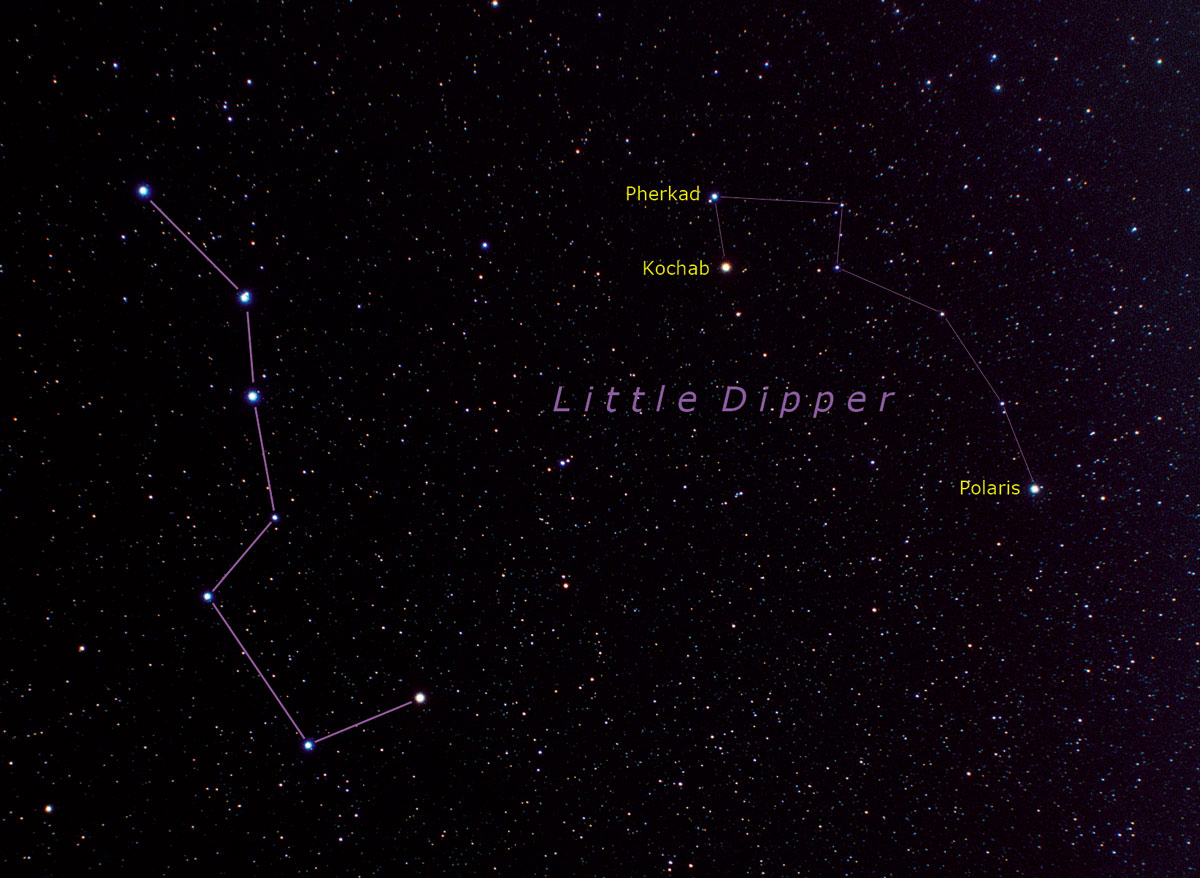

The Dippers as they’re positioned after dark at this time of year. If you can see the whole Little Dipper you have a darker sky than most of us. But 2nd-magnitude Polaris and Kochab are in much easier view, and 3rd-magnitude Pherkad is not far behind. Akira Fujii photo.

The Dippers as they’re positioned after dark at this time of year. If you can see the whole Little Dipper you have a darker sky than most of us. But 2nd-magnitude Polaris and Kochab are in much easier view, and 3rd-magnitude Pherkad is not far behind. Akira Fujii photo.

Polaris is the end of the Little Dipper’s handle. The only other Little Dipper stars that are even moderately bright are the two forming the outer end of its bowl: Kochab and Pherkad. These evenings you’ll find them to Polaris’s upper left by about a fist and a half at arm’s length, as shown above. They’re called the Guardians of the Pole, since they ceaselessly circle around Polaris through the night and through the year.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login