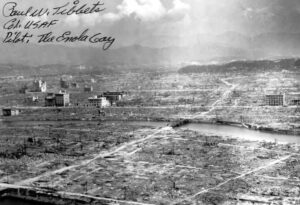

Special to CosmicTribune.com, August 6, 2025

Robert Morton, August 6, 1978

[Forty-seven years before the 80th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima, a Tokyo-based correspondent visited the family and neighbors of former journalist Yuji Yokoyama and filed this report.]

HIROSHIMA, Japan — Thirty-three years ago today, this city experienced hell as it had never been experienced before.

Shortly after 8 a.m., Miyako Yokoyama was standing just outside her front door talking to a neighbor and holding her one-year-old daughter in her arms. Her husband was gathering tools in anticipation of U.S. bombing raids as Japan’s defense weakened.

It was a beautiful morning, and the sky was a deep, clear blue. But for Hiroshima, the end of the world was at hand.

Looking up at the sound of an engine, the women glimpsed a high-flying plane.

Suddenly the sky turned bright orange, and a fiery wind hurled Miyako forward on top of her baby as the roof crashed down on top of them. Her husband died instantly and her young daughter, two years later. However, Miyako is still living today with her son Toshio’s family in a pleasant, air-conditioned home in a modern rebuilt Hiroshima.

Toshio was fighting with Japanese forces in Borneo when the world’s first atomic bomb reduced his hometown to rubble and claimed the life of his father. “Had he lived, I might not have been as independent as I am now,” Toshio said as he reflected on the role fate played that day. He said he still couldn’t understand how some people died while others had been miraculously saved.

For example, he recalled, when the bomb exploded, his father-in-law had just finished talking to a neighbor who had wanted to know what had happened at a town meeting he had missed. The two men had turned and walked away from each other. His father-in-law was blown about 16 feet into his house and lived; the neighbor died.

Saved by a shadow

Kayako Oda, 15-years-old at the time, was working in a needle factory located about 300 yards from the bomb’s hypocenter. Only minutes before the blast, she and a friend took a break and walked to an outdoor toilet located near the industrial promotion center — constructed with concrete and steel — which with its tower and dome survived the bomb and now serves as a memorial.

When the atomic bomb exploded some 1600 feet overhead, the temperature in the area approached that of the sun — 3-4,000 degrees centigrade. But because Kayako was in the shadow of the building at that moment, she and her friend somehow escaped the withering blast and made their way to one of the seven rivers in the Hiroshima Delta. From there she found the railroad tracks — stripped of trains — which led to her home. Her friend dropped dead along the way, and Kayako believes God saved her life.

Takefumi Yamaguchi, 71, occasionally wakes his family at night by crying out in his sleep. On Aug. 6, 1945, he was ironically digging an underground civil defense shelter at Ujina Harbor located about 2 1/2 miles from the hypocenter. Like thousands of others on the city’s outskirts who heard the wrenching boom and saw the mushroom cloud, he began walking to the downtown area to help.

Along the way, Yamaguchi said he saw so many people in the river he couldn’t see the water. Since he was a soldier, many blackened victims gathered around him pleading for water and salvation.

“They didn’t look like human beings,” he said. “Their skin was destroyed and some had no hair.”

For three days he searched for friends and relatives but was unable to find a single one because they were all living close to the hypocenter. Within a half mile radius of that point, the death rate was 96 percent.

Yamaguchi was ordered to burn and bury the bodies. He still worries that some of those he cremated were still breathing and thinks that’s why he can’t sleep peacefully at night.

“He felt the situation was like hell,” his daughter confides, “and he doesn’t like to visit the A-bomb memorial.”

Hiroshima’s tragedy has made the city a symbol for a number of disarmament and peace groups throughout the world. On Aug. 6, 1949, the municipal government passed a law making Hiroshima a “Peace City” and obligating the mayor to work for world peace.”

Mayor Takehashi Araki led a Hiroshima delegation of 50 to the recent U.N. Special Session on Disarmament in New York. In all, 500 representatives from Japan attended the session, U.N. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim proclaimed Aug. 6 as world disarmament day, but back at home last week, Araki said the world still doesn’t understand Japan’s point of view about nuclear weapons.

The governor of Hiroshima Prefecture, Ilirosho Miyazawa, reserves little sympathy for political groups that try to use the bombing for their own purposes. Referring the Gensuikyo and the Gensuikin organizations — backed by Japan’s Communist and Socialist parties respectively — Miyazawa labeled their activities as “unfortunate” and said, “I still do not understand what those people are trying to do.”

The two groups split in 1962 over the extent to which nuclear bombs should be banned. The communists felt the Soviet Union needed to develop the bomb as protection against the United States. But the socialists said all nuclear weapons should be prohibited. Now the groups are arguing over the issue of peaceful applications of nuclear power.

Help For Japanese and Korean Victims

Tadayoshi Murakami, a university astronomy professor and a leader of an anti-nuclear weapons organization backed by the more conservative Democratic Socialist Party, claims purely humanitarian motivations. “We don’t care about stopping the nuclear power plants, and we don’t think about the political problems in other countries,” he said in a telephone interview.

“We just try to help the casualties,” he said, “especially the impoverished Korean residents who were living in the city at the time.”

[An estimated 20% of immediate victims of the bomb were Koreans. In 1945, Korean had been a Japanese colony for 35 years, and some 140,000 Koreans were living in Hiroshima.]

Murakami’s organization, Kakkin, has constructed a small hospital in South Korea for the estimated 20,000 Korean bomb victims who have since returned to their homeland. The group also tries to help the approximately 20,000 Korean nationals still living in Japan to qualify for free treatment at the hospital for bomb victims in Hiroshima. In principle there is no discrimination against them, Murakami said, but in practice there is.

A spokesman for the World Friendship Center in Hiroshima acknowledged that the problem faced by the peace movement is disunity.

Like most other citizens interviewed here, his main concern is that the tragedy which occurred here never be repeated.

The importance of recalling the Hiroshima bombing, he said, is to impress on the world’s consciousness the reality of a nuclear attack — a horror experienced only by the Japanese and Korean residents here and in Nagasaki.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login